Max Cage is the heroic alter ago of the mild-mannered reviewer and commentator of comics, crime and all manner of pulp. He knows you have better things to do than read his musings but can’t imagine exactly what that could be.

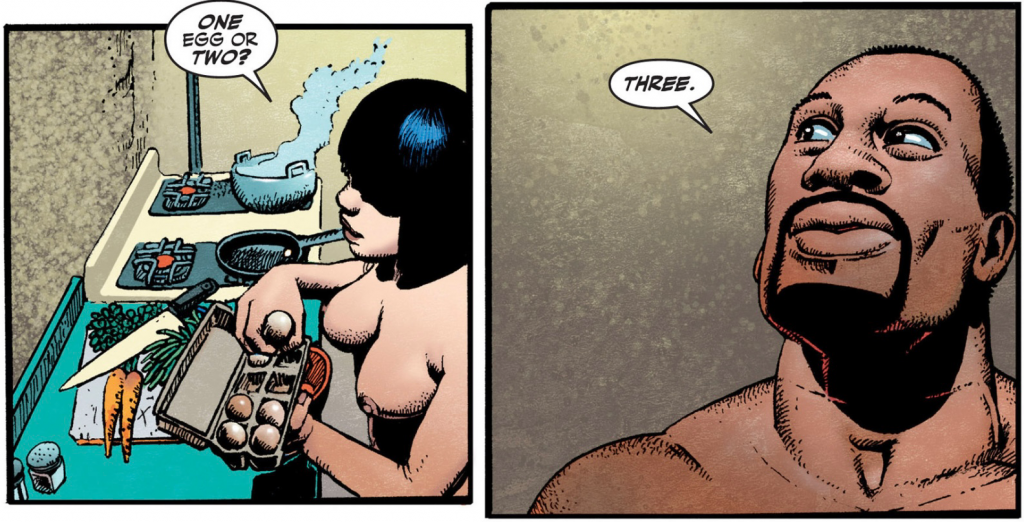

Wow, that line got me. Lines like that get me in general, I mean I’m a softie and I accept that but this time it was a real gut punch.

It wasn’t even the line, or the entirety of the panel, but the moment and all those before it in this comic, summarized completely in that sad panel. This is from 2002’s CAGE #1 by Brian Azzarello and the late, great Richard Corben.

Early-00s Marvel was doing all sorts of bold things, and getting some alt-comics greats like Richard Corben to play with their toys was one stroke of genius. Corben’s Den stories in random issues of Heavy Metal magazine were a gorgeous and baffling occasional find of my teenage years. I so much wanted to like Heavy Metal, hell the nudity alone was reason enough, but it wasn’t quite my thing. Respect to the talent in those pages, though! Richard Corben’s own talent was astonishing and his style was as unique and recognizable as his name. He works in a language of texture, teasing out warmth and depth through expressive small dot work and tiny pen-tip flicks. Traditionally coloring himself, some concessions had to be made to his usual method to accommodate Marvel production schedules, and the all-star Jose Villarubia steps in to color. This is no enviable task, but Villarubia is up to it, delivering a wonderfully textured and nuanced urban streetscape. Brian Azzarello is a crime writer who occasionally mixes in superheroes and is best known for the long-running series 100 Bullets, about which future column space will certainly be devoted.

Before discussing the story — it came out in 2002, it’s not like this is exactly topical — I have got to lay out the basics, then some thoughts, about Luke Cage. In prison for a crime he did not commit, Carl Lucas becomes a test subject for mad-scientist fuckery and gains superpowers. He breaks out and reinvents himself as Luke Cage, Power Man, Hero for Hire because modesty isn’t his strong suit. If the stainless-steel headband and gold satin shirt collection hadn’t already clued you in. It was 1972 and this was all intentional, for there was no action-film movement that Marvel wouldn’t take advantage of. It was Blaxploitation’s turn, and the comic page was here to translate it.

Without realizing it, creators Archie Goodwin and George Tuska were entering into the record something about systemic racism that I am not entirely sure that I can parse. I feel a certain discomfort in the dismissal of Cage’s crime having been a set-up; it smacks of allowing him to become a hero because he’s “one of the good ones”, icky as that is even to type. I also acknowledge that for most of his comic history, Cage has been written by middle-class white dudes — like myself, yes — and there’s something complicated in how the character appeals to me. Maybe in part because it’s filtered through a lens I am conditioned to accept. All that said, this is crime comics and that’s why we’re both here, so let’s get on with it.

In making something tied to a cultural phenomenon with an obvious expiration date, in this case Blaxploitation, instead of dooming the character it somehow freed him. As the music and attitude that was the film movement (to put it generously) evolved into the more culturally significant hip-hop and beyond, so was Cage transformed. The result is that he as a character and concept was given a chance to hang around, get noticed and appreciated. For a new generation of kids he was a favorite B-lister and to some, the one character that looked liked them, their own Peter Parker.

While a hero might start off designed to appeal to a specific group of people for a specific reason, a really inspired one will appeal just because they’re outstanding and Luke Cage was exactly that. Chip on his shoulder, quick to anger and throw down, taking no crap from nobody, he reflected the confused, impulsive turbulence of our adolescence in a way many others couldn’t. He used cool-sounding curse word stand-ins like Sweet Christmas and was so tough he wore this giant honkin’ steel chain for a belt! In an only partly tongue-in-cheek early issue, he is hired for a job and cheated by Doctor Doom; Cage makes his way to Latveria, the European nation of which Doom is ruler, to smack those bills loose. You don’t rip off Power Man!

Teamed up with Kung-Fu craze survivor Danny Rand, Iron Fist, and still in his Funktown USA/Sweet Christmas phase until the late 80s (when I developed my man-crush, coincidentally). Cage disappeared for a time and came back in black leather with a fresh, new barber cut and rejecting the Power Man name. It was ‘92 and we were far too serious for the gold satin pirate shirt, dammit! That lasted until ‘96 when the demands of nostalgia regressed Cage partly back to now sporting colorful tee-shirts and yes, it did bring back that fantastic steel headband.

In 2002 it was time to update the icon and Azzarello and Corben did exactly that. Taking the character into a very rare foray into more or less straight crime story, Azz took complete advantage of the MAX imprint Marvel published this under, encouraged as the creators were to produce very adult takes on characters. I wonder if he couldn’t have expressed this newly adult approach a little better than by thrusting Cage into strip clubs and into bed with Dixie every so often.

Cage’s ‘don’t care’ street fixer front is cast in some doubt when the mother of the murdered girl says, “I heard you help people that need it.” We have a hero’s journey dangled before us, but don’t get too comfortable! Azzarello’s writing tends to have a decidedly noir bent, and noir is bad news for everybody. The dead-girl bait and Cage’s approach to the situation starts off as pure hard-boiled PI story with ghetto trappings, but then we move into a very different type of crime tale as Cage starts smelling a big payday. There are no heroes in noir, after all, and while we’re teased that this might be his complicated way of doing good deeds, it’s hard to be certain about much with this character.

Being completely honest here, this isn’t Azzarello’s best work. He is an exceptional crime writer and in the future we’ll discuss other examples of his work that better reflect this, but Corben is doing the heavy lifting on getting this book pretty high in my esteem. That the hero’s journey is teased but never realized is unsatisfying and even in this ‘never change’ medium of corporate comics, I was expecting more of a character arc. This was always billed as a miniseries and Marvel wasn’t shy about saying that stuff under the MAX imprint didn’t technically matter, setting a ‘creators go nuts’ vibe but also an implication that stuff would be finite. If there’s any real growth in the Cage character from the first page to the last, I missed it. Azzarello creates great tension and gives us over-the-top action payoffs regularly, but it’s more because he’s keeping a storytelling rhythm going than meeting the demands of a gripping narrative. Cage’s approach to the job wanders between smacking people around but not bothering to learn much, and sitting around drinking beer. The factions he wanders between are rival street gangs plus the Mafia, and he ends up working for each of them at some point. It’s never made apparent if he really wants justice for the murdered girl or if he’s just chasing cash; without that distinction it’s hard to figure out how to identify with Cage. Is he reluctant hero or antihero? Even his closest relationship shown, with the Korean bartender Dixie, is little beyond casual sex and a softball pitch to artist Corben.

Visually, Richard Corben delivers Luke Cage rendered unmistakably as a Black man in his features where so often in the past he had to rely on a big Afro and chocolate skin color. Corben’s Cage is obscenely diesel in the tradition of his most well-known creation, Den… if less naked. Shirtless under a sleeveless bubble vest, chest draped with chains, eyes hidden behind shades, this is a gangsta antihero. Oddly for a bulletproof man, this all seems to be armor as well. When we see him without it in Dixie’s apartment, he is drawn tenderly and slightly vulnerable.

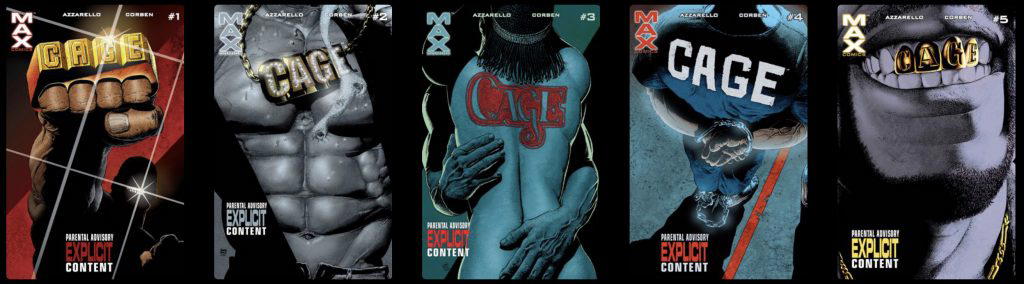

Corben’s covers are breathtaking examples of design and his trademark rendering style that owes as much to texture as to line work. On each cover, the comic title has been incorporated into the image; the first issue is a close-up of his fist, encased in vanity knuckledusters, if that’s such a thing. Light glints from Cage’s gold tooth, face in shadow and his grin the only feature visible. Another close-in image of that grin closes out the covers on the fifth issue, his personalized gold-teeth grill delivering the logo. That one might be my favorite, but the caged-Cage cover image of #3, in his prison jumpsuit, is also arresting. These covers are unapologetically in the reader’s face and standing too close. Even those who didn’t know Corben’s work could see that these covers rocked.

Behind those covers, Corben continues to display a style that is kinda like Robert Crumb in how it’s simultaneously ugly and sexy and exaggerated. Cage’s arms hang at his sides, grotesquely veiny and muscled and phallic and not a little disturbing at times. The audience (guys like me, the intended sales audience at the time) is not meant to identify with this man, to feel like you’re his pal, or could even be. With every page, me and my middle-class white comfort were put back on my feet, unbalanced, nervous and voyeuristic.

The action scenes come in several flavors; one two-page sequence features Tombstone gunning down crowds of foes, something like 50, 100 hand-lettered BANG and BAM sound effects surrounding the action. This is something I would see once in a while in Heavy Metal-era indy comics, but I don’t really know why it’s a thing. I respect the use of the effect. In another couple of fight scenes Cage is sorely tested by another super-strong hooligan, Man Mountain Marko (horrifically, wonderfully ugly here). Those scenes are fast and mean with the combatants entwined, bloody and struggling. Blows they land do terrible, destructive damage to one another, rendered with liberal splashing of blood and deforming of faces. That cartoonish edge in Corben’s art, that overall exaggeration that flexes and wanes, works to keep the ugliness and violence silly enough to keep from being off-putting. When it’s sex appeal Corben wants to put across he slips into that mode easily, softening Cage’s resting-thug face with an occasional moment without his ever-present shades, skullcap and headphones.

Minor digression, gonna nerd out here just a sec. The last page of the last issue could have been drawn by Steve Dillon, it looks so much like him! In art style and page layout, and that Fourth Wall-breaking eye contact with the reader. I’d never seen much style similarity between the two before but I suspect Dillon, also gone way too soon, may have counted Corben as an influence.

Ultimately, the script is a skilled delivery vehicle for spectacular late-career art storytelling from a small-press master whose work we’ll never see again. According to the the fan-fiction version in my head, Brian Azzarello intentionally wrote a comic that wasn’t a great story but in his genius he knew would give Richard Corben opportunities to make CAGE a crime masterpiece defining his brief Marvel career.

Should you want to read Luke Cage’s brief foray into hip-hop crime comics, it was published as a 5-issue miniseries called CAGE in 2002 and those are actually easy enough to hunt down today. You can also enjoy it digitally from your favorite legal e-comics seller, should that be your thing, or in a variety of easily accessible collected print editions like the ooh, pretty oversized hardcover I just re-read. Azzarello continues to write crime and superheroes and occupies a nice niche right where the two sub-genres blend. Sadly, Richard Corben passed away in 2020 at 80 years of age. I hope he knew what a titan he was and still is considered.

In mainstream Marvel stories, Luke Cage’s aggressively gangsta presentation mellowed and streamlined as he took a more decidedly super-heroic approach to life for a while, then transformed again as he became a Dad and got hitched. At the same time, he took a Marvel Cinematic Universe-adjacent turn with Mike Colter basically jumping off the comic page and into the Netflix series. It will be interesting to see what form he takes in his next evolution.

Max Cage, for Shotgun Honey

Investigating the murder of a teenage girl, Cage suddenly learns that a three-way gang war is underway for control of the turf he calls home. And what better way to disrupt the stalemate than offering his services to the highest bidder?

Max Cage is the heroic alter ago of the mild-mannered reviewer and commentator of comics, crime and all manner of pulp. He knows you have better things to do than read his musings but can’t imagine exactly what that could be.